Your Team, Part B

Last week, we talked about how important it is to make sure your content and cover are solid in order to honestly compete in the indie market. There are a few more parts that require your attention, though, before we can say that we’re truly ready to rock the literary world.

Book Designers

You have likely never developed a strong opinion about fonts until you’ve talked to a book design nerd – and I mean that you will develop strong opinions about fonts after talking to a book design nerd because their particular ailment is highly contagious.

Book design is one of those things that you don’t think about when it’s done well, but you will absolutely notice it if it’s done poorly. At the RWC 24, I asked my audience what kind of font would go with which kind of genre. A long-careered journalist said Times New Roman for pretty much everything, and while TNR is the go-to for journalism – and, by extension, scientific journals – it is painfully, grotesquely boring in a fiction or literary context. Someone suggested Courier, and that’s great for a hard science fiction novel. Garamond is a softball hit for anything fantasy or romantic, but there are thousands if not millions of fonts, all with slight variations, that can speak to the spirit of a story.

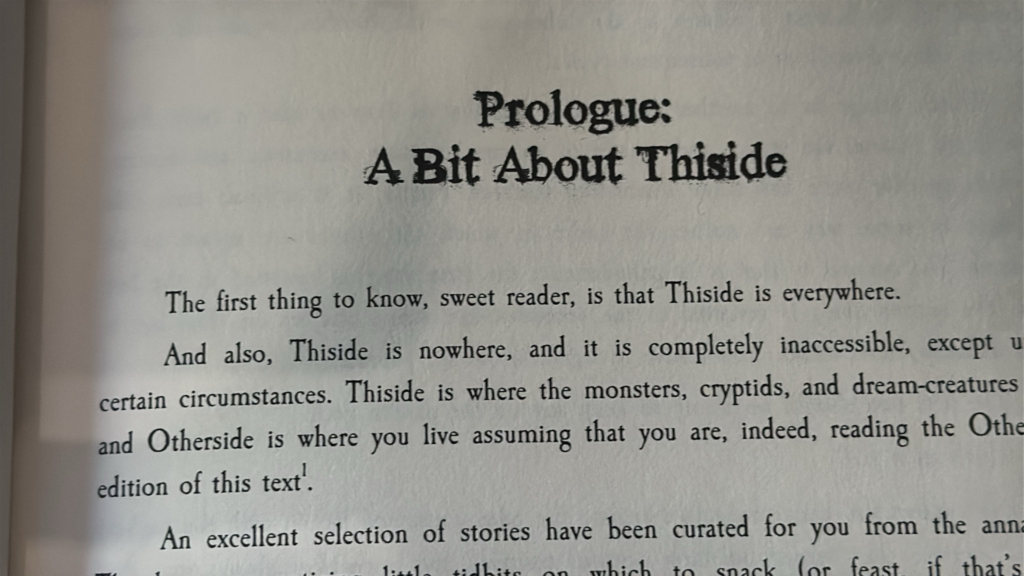

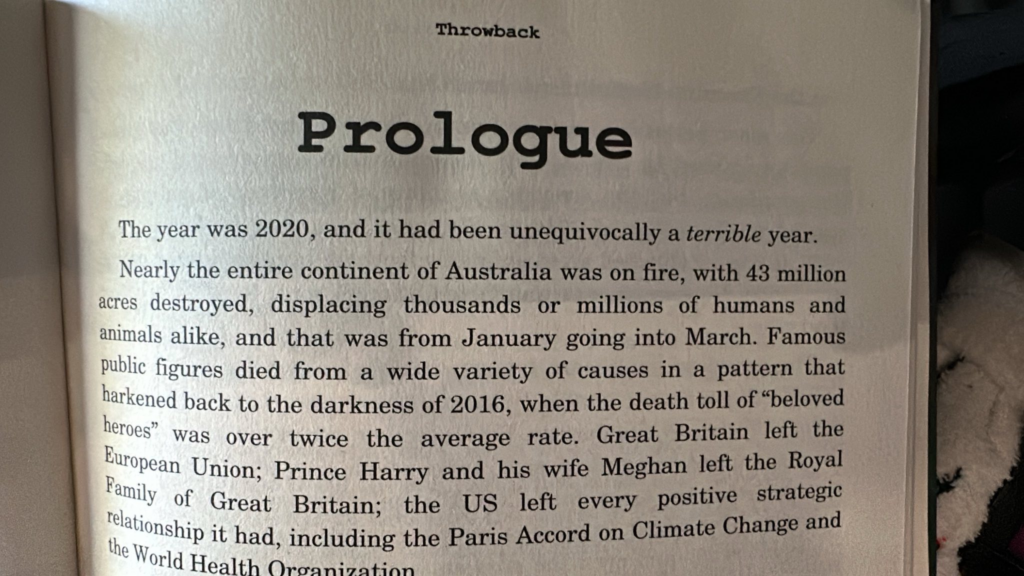

For instance, in Thiside of Anywhere, I used Calson Antique, a venerable and lovely serif font with a classic feel designed in 1894 by Berne Nadall, because I wanted the reader to feel like they were reading an ancient story that was translated somewhat into a modern context.

In Throwback, I used Century Schoolbook L by Morris Fuller Benton, originally designed in 1924, to occur to the reader as familiar but just a little different, a little off, much like the world would have felt to the people who were unceremoniously dumped ten years in the past. I used Times New Yorker (D.O.C.S.) for Thiside chapter headings because it has a slightly creepy feel to it, but I used Nimbus Mono PS (URW Studio, 1984) for the headings in Throwback because those stories were like little documentary pieces, and mono-space fonts feel official and important, maybe even authoritative.

Font selection is a subtle art adjacent to graphic design, and it matters. (That’s a pun, you just don’t know it yet.) Book design is also where the dinkus is determined. That’s the official word for the symbol that goes between sections in a story. Some people use blank spaces, other use typed bits like “* * * * *”, and still others use images or illustrations.

Now, here’s where we have to talk about format – as in, what the actual book is going to be in someone’s hands – because book design is different for digital versions from hard-copies, and with hard-copies, there is significant difference between the paperback version and the hardcover.

Fonts matter the most in hard-copies because the reader can’t change them at a whim. Digital copies may have a default font determined when you first lay it out – and I strongly suggest that you make that choice conscious and deliberate – but be aware that your reader can easily change the spacing, the font, the color, the flow… and that’s excellent because that makes your story more accessible to people. All that customization, though, means that you should never, ever have a blank line for a dinkus; the section break can happen anywhere on an e-reader, and you need to accommodate for that.

The tools of a book designer are the desktop publishers. The most famous of these are InDesign and MS Publisher (no links, they get plenty of traffic on their own), but there are lots of other up-and-comers that do beautiful work. Affinity Publisher is excellent, QuarkXpress is still a thing, LucidPress has become Marq, and there are plenty of others. Not every app works on all platforms, some are subscription-based (Marq) while others are one-time purchases (Affinity), and there are also open-source freeware platforms out there as well, which is mainly just Scribus. (You know how much I love free and open-source, and also alt-platform-supportive.) Many of these will prepare your manuscript for either print or digital formats, but not all of them. Scrivener is an app that functions both as a word processor/world-wrangler and an epub designer on Windows and Mac, or if you know anything about CSS (cascading style sheets) and HTML, you could try your hand at Sigil.

None of these programs are super-intuitive out of the box. All of them have their quirks and idiosyncrasies, their strengths and weaknesses, and their learning curves – which is why hiring someone who already knows how to do all that is a good option to keep in your back pocket. Someone who is experienced in book design knows which front and back matters to include in what type of story, where to use what kinds of justifications, whether to adjust the kerning by hand in certain places, getting the page numbering and chapter spacing just right, and so on.

Can you learn how to do this yourself? Sure, anyone can, but it’s going to take a lot of time and energy when you could be writing things. And also, most book designers have already purchased their favorite desktop publishing software so that you don’t have to. Figure between $150 and $500 for a book that has minimal illustrations, but anything with lots of graphics and complex layouts can run as much as $5000. A simple search for book designers will take you to a plethora of options for hire, but remember to always look at samples of their work and get examples of what they’ve already published before shelling out the big bucks.

Nerds (Research)

I’m including this as its own heading as a nod to the first presentation I gave at the RWC 24. My sweet, lovely units, research your shit before you hit “publish”.

I shared with you some world-wranglers – Campfire Pro, World Anvil, and so on – and I sincerely hope you remember about Zotero. You know to look stuff up on Schoogle, and to use UnPaywall and 12ft.io to find the full versions of articles instead of just relying on the abstracts. The single most important thing that I wanted you to come out of that presentation with, though, was to arm yourself with the Power of CRAAP, the method by which you will evaluate the credibility of a source by examining the Currency, Relevance, Authority, Accuracy, and Purpose.

So, why am I putting “researchers” on your team roster?

Because we are, all of us, without exception, biased.

We each have a worldview that we believe to be true, and when we discover that something we believed might not be true, it causes us distress. This can have major or minor consequences in our daily lives, but it will have monetary consequences if your book is published touting something to be true that can be easily and specifically debunked. (Or, we hope it would. That’s not always the case, I guess, depending on the audience…)

If you want to write a good book – yes, even if it’s science fiction or fantasy – you have to start with verifiable facts and things that people already know are true in order to lead them to believe in things that aren’t so true. Exothermic dragons don’t make a lot of sense if they’re also fire-breathing. In space, no one can hear you scream – or can hear your spaceship explode. But also – and I’m particularly adamant about this – accurate research is vital to writing characters with personality disorders and disabilities. PLEASE do not use the DSM-V as the sole source of your research for what might make a person “crazy” because it’s written exclusively for (crappy) diagnostic purposes. It does not describe lived experiences or actual social impact.

So, the “nerd” in question might be you digging in deep to a topic, but you should also get some other eyes with knowledge and experience in your non-personal-content areas on it. This is in the same vein as hiring sensitivity experts to make sure that your depictions of other cultures aren’t offensive, and that you’re not accidentally advocating for some kind of massive atrocity. Don’t just rely on the internet: call (or email) experts and ask them questions. Get your facts right so that your fiction hits right.

Merch and Marketing

Next week, I’m going to get into the deep nitty-gritty of all the different pieces of what you need for a marketing plan, but for the purposes of this part of the series, let me say, earmark some cash for a merchandise and marketing budget.

Yes, this might include things like social media boosts, but even before you get to that point, you need to have a few basic items that will set you apart as a Professional Author. Really good business cards feel like a relic of the past, but they matter. Bookmarks seem like throwaway items, but they matter. Stickers are always popular so long as they’re entertaining, so think about what your catch phrase or hook might be. Is there a distinctive character? Is there a fictitious business or location? Any of these things can remind your audience of your story.

For this, you’re going to need a graphic designer. Maybe the person who did your cover art is still available for this sort of thing, but more likely, you’ll need to find someone who specializes in the type of art that you want on that sticker. Experiment with different styles and fonts. Then you’ll need a sticker printer: you can get die-cut stickers, oval stickers, square stickers, triangle stickers… I’m not going to link to all the different sources because each one is a little different, and this is definitely a You thing. I used “stickers print on demand” as my search string and found dozens of options. What about t-shirts? Eh, they’re not usually a good investment for the first few books, not unless you do a lot of conferences and conventions with an actual booth. Pens are nice, notebooks, whatever little item is going to resonate in such a way that it connects your audience with your story.

Now, do you charge for these things, or do you give them away? That is entirely up to you, but understand that from a tax perspective (in the US), giving away stickers is a Cost of Doing Business (Advertising/Marketing Budget) and therefore an Expense, where selling things requires a sales and usage tax permit and quarterly filing in your local and state municipality, and is thus Revenue. I am not an accountant, but I am a cheapskate who likes minimizing my tax burden. (I should probably include the price of CPAs in this list at some point, but that might be getting a little ahead of ourselves.) The story is the actual product; the merchandise is just there to point people to the story.

Because if you’re indie publishing with the intention to be successful, to make money, to quit your day job, you have to approach it as a business. You are investing time and real money into developing a product, and that product needs to perform well in the market for you to recoup your costs and turn a profit.

Your Business Is Your Business

I cannot stress how absolutely, mind-bendingly important it is for you to approach indie publishing as a professional. I mean, yes, you should be approaching writing for money from a professional position anyway, but when you’re the one responsible for the entire success of the project, beginning to end, you have to really wrap your head around the reality that you’re the one responsible for the entire success of the project, beginning to end.

One of the skill sets that I developed over the years that does help me a great deal in my indie publishing journey, both as an author and as an impending micro-press, is as a project manager. Wrangling people to fulfill their tasks by a certain deadline, being very specific about what I need, working with contractors to get the end product right, these are all things that I have done for years, and I am reminded frequently that not everyone can live and breathe project management like a second skin. Thus, if you’re serious about being at the helm of your own indie journey, definitely look into some project management methods. You don’t have to go full PMP or become a Scrum Master or anything, but certainly learn the basics of planning a project, identifying the assets you’ll need, and then satisfying those needs as efficiently as you can.

Writing is a project-based activity. Each story, poem, novel, script, or even collection is its own unique thing. We do not write the same thing over and over again, we write new things every time we sit down. We might continue in the same world, but the story is evolving and growing.

If we start off with a project planning mindset – even if we as writers are total pantsers – we also give ourselves a structure by which to know when something is done. When we know that there is a whole team of people to back us up, to give us our guardrails, and to help us make the best story possible, we are relieved from much of the stress that comes from turning our creative endeavors into revenue streams.

It’s okay to have a team. You need a team.

Get caught up: Part 1 – Part 2 – Part 3 – Part 4 – Part 5 – Part 6 – Part 7

1 thought on “Indie Publishing Like a Semi-Feral Goblin With a Business Degree, Part 3”